A Regional History of Indigenous Land Dispossession

HNLF is primarily geared toward non-Native people living on the ancestral territory of the Ho Chunk/Winnebago, Ioway, Meskwaki/Fox, Sauk, and the Oceti Sakowin nations to offer reparations by contributing to the Great Plains Action Society. However, we welcome financial contributions from people living anywhere, especially in the Midwest! Consider starting an Indigenous Solidarity Fund in your own region!

“This history is not your fault, but it is absolutely your responsibility.” -Nikki Sanchez

Ho Chunk/Winnebego

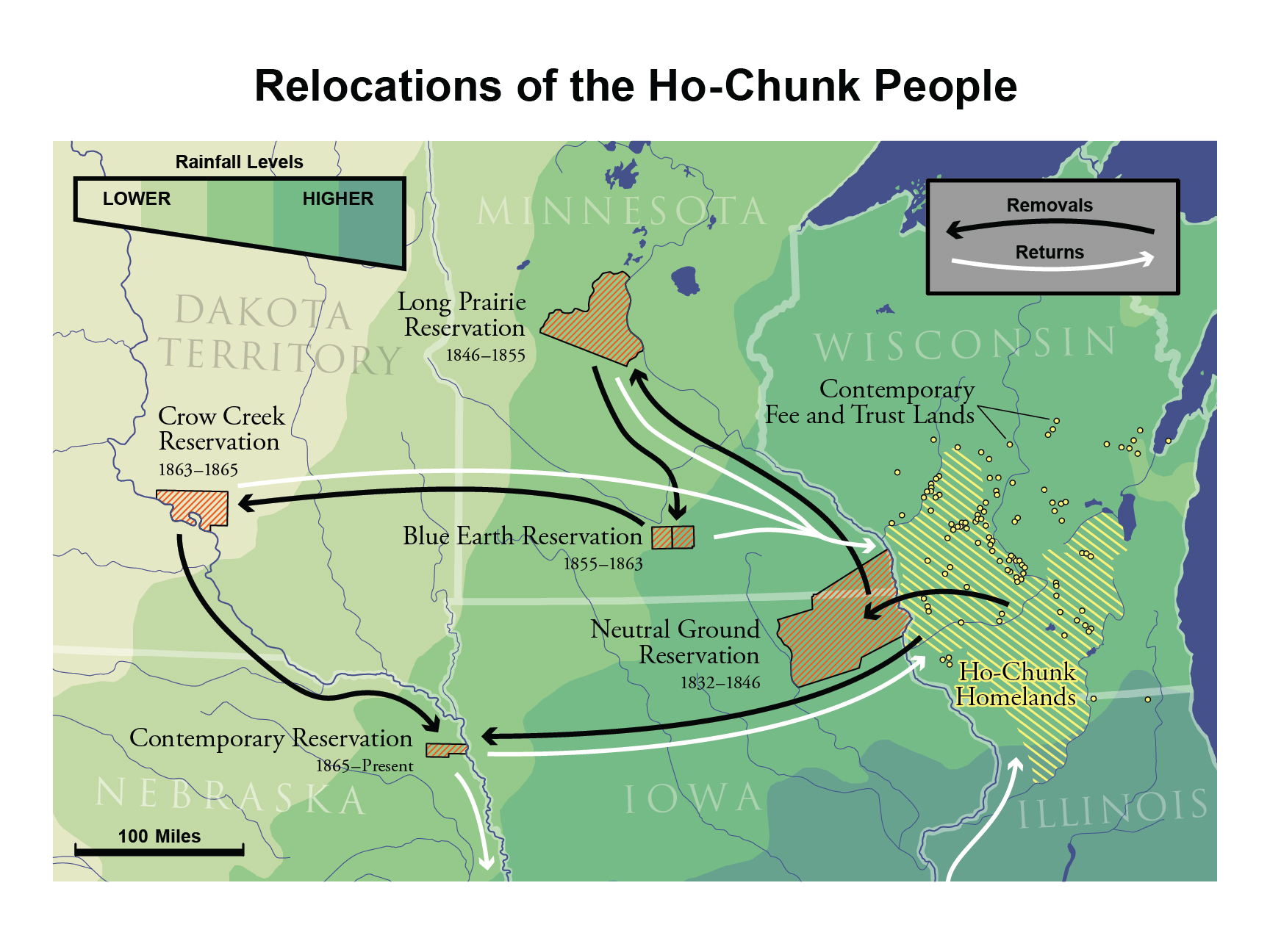

The Ho-Chunk have been living in this region since time immemorial. The Ho Chunk refer to the unglaciated region of the Midwest (which many non-Native people call the “Driftless”) as the “Refuge,” for it was here where they survived the last Ice Age over thirteen thousand years ago. In the 1800s, the Ho Chunk faced removal, through what they call the “Trail of Death,” no less than five times.

Map by Cole Sutton

The Ho Chunk were forcibly marched to several different locations, shown in the map above. Eventually, members of the Ho Chunk nation were forced onto a reservation in Nebraska, where many remain today, and where they are now known as the “Winnebego Nation of Nebraska.”

Some Ho Chunk resisted removal by repeatedly returning to Wisconsin. In 1881, Congress finally passed special legislation granting individual Ho Chunk in Wisconsin forty-acre homesteads. Native historian Patty Loew writes, “Although the lands were inferior, most Ho-Chunk eked out an existence hunting, gathering, fishing, and gardening and occasionally hiring themselves out as farmhands.”

Though the Ho-Chunk remain in Wisconsin today, Loew writes, “Many Ho-Chunk members believe the greatest challenge facing the tribe remains their lack of a land base.”

Ioway

The Ioway people are called Báxoje in their own language. They are historically related to the Ho-Chunk people and share ancient roots in the Upper Mississippi Valley. Ancestors of the Ioway nation lived on both sides of the Mississippi River in present-day Iowa, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. The nation had major villages on the Upper Iowa River in the 17th century.

European colonization during the 17th and 18th centuries forced Indigenous people from the Atlantic Coast and Great Lakes west toward Ioway lands. The Ioway nation accommodated Meskwaki and Sauk refugees in their territory. As more people arrived from the east, the Ioway people gradually moved their own villages southwest toward the Des Moines and Missouri Rivers while still maintaining a claim to ancestral land along the Mississippi.

In the 1825 Treaty of Prairie du Chien, the United States officially recognized that the Ioway nation had equal rights with the Sac and Meskwaki nations to a large territory stretching all the way from the Mississippi to the Missouri Rivers, including most of the present-day state of Iowa. Despite this acknowledgement, the U.S. proceeded to acquire the land in treaties with the Sac and Meskwaki nations without including the Ioway nation in the negotiations or payments. In 1837, a delegation of Ioway leaders visited Washington, D.C., to protest their treatment and reassert their land claims. The leader No Heart of Fear presented a hand drawn map of the Upper Mississippi Valley showing the Ioway Nation’s deep connection to the region. Although the U.S. agreed to grant the Ioway Nation a small annuity for its land losses in the 1838 Treaty of Great Nemaha, the Ioway people received less compensation than many other Indigenous nations with claims to the region.

Faced with the American seizure of their homelands, the Ioway people were forced to resettle during the 1830s on reservations in present-day Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. The Ioway people maintain sovereign governments today as the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska and the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma.

Oceti Sakowin

The Oceti Sakowin is a confederation of seven Dakota and Lakota nations, often called “Sioux” in historical documents. The seven divisions of the Oceti Sakowin are the Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Wahpeton, Sisseton, Yankton, Yanktonai, and Lakota.

The Dakota people have roots in the woodlands area between the Mississippi headwaters and Lake Superior. In the 1825 Treaty of Prairie du Chien, the U.S. recognized the Eastern Dakota (Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Wahpeton, and Sisseton) people as the rightful claimants to a large territory including what is now west-central Wisconsin, far northern Iowa, and southern Minnesota. The United States acquired most of this territory in treaties in 1837 and 1851, but as was often the case, Americans failed to uphold their treaty pledges. The U.S. Senate refused to ratify the portion of the 1851 treaties granting the Eastern Dakota people a permanent reservation in exchange for their ceded lands, while much of the money promised in the treaties was redirected to fur traders and other white merchants. These broken promises pushed many Dakota people toward starvation and culminated in the 1862 U.S.-Dakota War.

Following the 1862 war, the U.S. pursued a policy of ethnic cleansing against the Dakota people. Men, women, and children were forced into concentration camps at Mankato and Fort Snelling, Minnesota. The U.S. executed 38 Dakota men at Mankato on December 26, 1862, in the largest mass-execution in American history. American authorities sentenced around 300 other Dakota people to military imprisonment at Camp McClellan in Davenport, Iowa, where over 100 died of disease and malnourishment. The remaining Dakota people in Minnesota were packed onto steamboats and forced to resettle in present-day South Dakota, in the territory of their Lakota relatives. The U.S. Army continued to pursue the western members of the Oceti Sakowin confederacy in wars throughout the 1870s-1890s.

Dakota and Lakota survivors of U.S. colonialism preserved their people’s sovereignty and traditions despite the assault on their lives and homes. By the 1890s, a few Dakota communities regained small land holdings in Minnesota. Even so, the vast majority of the Oceti Sakowin land base today is on reservations in North and South Dakota. Today around half of the Dakota and Lakota population lives off-reservation in cities around the Midwest and beyond.

Meskwaki and Sauk (Sac and Fox)

In the early 1700s, fleeing the attempted genocide of their people by the French further east, the Sauk and Meskwaki found a homeland along the Upper Mississippi, where they established villages. In 1804, William Henry Harrison, later the 9th president of the United States, used liquor to trick a small delegation of Sauk and Meskwaki people - none of whom had the authority of their nations to sign treaties - into signing over 50 million acres of land east of the Mississippi. In return, the nations received $2,000 in goods, and were promised an annual payment of $1,000. Of this fraudulent “treaty” the Sauk leader Black Hawk would later write, “I will leave it to the people of the United States to say whether our nation was properly represented in this treaty. Or whether we received a fair compensation for the extent of country ceded.” A decade later, following the War of 1812, white Americans in search of lead descended into the region. By 1825, 10,000 miners had illegally invaded the region.

In 1830, Andrew Jackson passed the Indian Removal Act, demanding that all Native Nations living east of the Mississippi move west. Emboldened by this Act, as well as by the fraudulent treaty of 1804, white settlers felt entitled to Native land. Black Hawk, after returning to his village of Saukenauk (currently Rock Island) after hunting in central Iowa, reported that “…three families of whites had arrived at our village and destroyed some of our lodges and were making fences and dividing our corn fields for their own use… I went to my lodge and saw a family occupying it. I wished to talk with them but they could not understand me… the greater part of our corn-fields had been enclosed… What right had these people to our village, and our fields, which the Great Spirit had given us to live upon?” Black Hawk and others resisted this flagrant land theft. The Sauk refused to leave their homes, land, and fields. In 1832, in what is known as the Black Hawk war, he and his group were chased north into Wisconsin for 16 weeks. Though they repeatedly tried to surrender, in August 1832 the US militia massacred 150 men, women, and children as they tried to cross the Mississippi River near the town now named “Victory.” In the wake of the massacre, the Meskwaki and Sauk were pushed further west and forced to sign the so-called “Black Hawk Purchase” in which the US government grabbed six million acres of land for just 11 cents an acre. In the face of unjust removal, in 1857, a few Meskwaki and Sauk purchased 80 acres of land in what is now Tama, Iowa. The Meskwaki and Sauk now own this land, the only Indian settlement in the country, which now encompasses more than 8,000 acres. There they are reintroducing bison, establishing food sovereignty programs, and revitalizing their language.